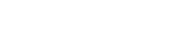

Warren Beatty's Dick Tracy is the bright, cheerful cousin to Tim Burton's Batman. When Tracy was released the year after Burton's film, it felt something like a repeat. (It didn't help that Danny Elfman scored both pictures.) But now, after over two decades of tortured heroes in dark films inspired by comics and graphic novels, Tracy's sunny retro look is positively refreshing. The late Chester Gould, who created the character and drew the strip for years, was reportedly an impediment during the film's long gestation period, but it was Gould's distinctive vision that ultimately made Tracy unique. No one would ever mistake Tracy for a film based on a Marvel or D.C. character.

The square-jawed Dick Tracy was Gould's ideal of the tough, righteous cop who couldn't be bought, scared, or thrown off the track, and who could always be relied upon in a crisis. Tracy's foes were always distorted lunatics because in Gould's imagination you could see criminals for what they were: warped and dangerous. His cops didn't talk much, but his criminals were full of chatter, much of it repetition of catchphrases. It was Gould's way of conveying that they lived in their own world.

It seemed ironic at the time that Warren Beatty, who began his career playing rogues and criminals (most famously, Clyde Barrow in Bonnie and Clyde), should end up portraying one of fiction's most stalwart cops. But one glimpse of that famous mug under a yellow fedora was all it took to convince Tracy fans that Beatty was their man. After numerous writers, many potential directors, and several casting changes (notably, the replacement of Sean Young by Glenne Headly in the pivotal role of Tess Trueheart), Dick Tracy finally went before the cameras under Beatty's notoriously persnickety eye, which drove everyone crazy. A tumultuous production left rumors in its wake of a two-hour and fifteen-minute "director's cut" shortened at the behest of then-Disney president Jeffrey Katzenberg, but its existence has been consistently denied. Reliable reports indicate that the current version, which runs one hour and forty-five minutes, is Beatty's cut.

Dick Tracy takes place in a lustrous metropolitan landscape where the police have been holding their own against crime, but only barely. One gets the sense that, without Dick Tracy (Beatty), the battle would be lost. This wouldn't be an entirely unwelcome result to Tracy's long-suffering girlfriend, Tess Trueheart (Headly), who always gets abandoned when Tracy is summoned by a call on his trademark two-way wrist radio. Let someone else look after the city for a while, thinks Tess. Her man can take a desk job. Tracy loves Tess, but the running joke is that the man who is fearless when facing a hail of bullets becomes timid when staring into the eyes of the woman he loves.

The film's plot is driven by the efforts of top hood Big Boy Caprice (Al Pacino) to seize control of the city's rackets. As a first step, Big Boy has his enforcers, Flattop (William Forsythe) and Itchy (Ed O'Ross), mow down the chief lieutenants of rival Lips Manlis (Paul Sorvino) at a card game. Then it's Lip's turn to go, leaving Big Boy in possession of a new headquarters, the swanky Club Ritz, and a new girlfriend, the Club's star attraction, Breathless Mahoney (Madonna), a hybrid of ingénue and femme fatale.

Tracy's private life is complicated by The Kid (Charlie Korsmo), an orphan whom Tracy chases down after the boy steals a watch, but then rescues from the cut-rate Fagin to whom The Kid reports (Steve Epper). Tracy and Tess look after The Kid-Tess calls him "the eating machine"-and Tracy keeps not sending him to the orphanage, even though "it's the law". Meanwhile, The Kid keeps following Tracy on calls. He proves useful, too.

By using Big Boy's plan to take over the rackets as an excuse, the script stuffs the plot with a dozen or more Gould characters that Gould himself never brought together. Beatty's clout as a producer allowed him to get an amazing cast, even though many familiar faces are hidden behind elaborate make-up and costumes. Dustin Hoffman is almost unrecognizable as Mumbles (so named for obvious reasons), as is Dick Van Dyke as D.A. Fletcher. Mandy Patinkin can be spotted as Breathless' piano man, 88 Keys, but he's never looked so homely (and in the world of Chester Gould, looking homely is a bad sign). Blink and you may miss Beatty's old Bonnie and Clyde co-stars Estelle Parsons and Michael J. Pollard as, respectively, Tess's mother and a cop named Bug Bailey. And see if you can recognize the familiar voice of familiar bad guy R.G. Armstrong behind the elaborate wrinkles of Pruneface.

The only hood who isn't hidden behind major makeup is James Caan's Spaldoni. In a scene rife with subtext, Spaldoni challenges Big Boy at a conference of the city's bad guys. Again, this is Gould's world, so that when the former Corleone Brothers clash, the one with the least distorted features behaves more honorably. Of course, in gangland, honorable behavior is not rewarded.

All of this plays out in a world designed to look like a comic strip, but a Chester Gould comic strip. Richard Sylbert won an Oscar for his inventive production design that relies on vast expanses of the basic colors that Gould used in his panels: red, blue, yellow, orange, green, and purple. Costume designer Milena Canonero created a variety of patterned but monochromatic looks so that every crook in Tracy became his own variation of Jack Nicholson's Joker. (Indeed, Nicholson's purple-clad prankster would have fit right in.)

Matching the colorful surroundings is the jazzy soundtrack with songs by Stephen Sondheim. In a varied and unpredictable career, Sondheim probably never expected to compose songs for a major pop star. Madonna doesn't have the Broadway-trained diction for which Sondheim usually writes, but she delivers his tricky lyrics with the enthusiasm of the nightclub chanteuse she's playing, and they're the perfect accompaniment to the montages of crime and law enforcement assembled by Beatty and his editor. The film doesn't set a definite time period, but it feels like the Roaring Twenties, and even law enforcement is a blast. Just ask The Kid.

Al Pacino's portrayal of Big Boy Caprice has often been criticized as "over the top" and "scenery-chewing". These criticisms started when Dick Tracy was first in theaters, and they've never disappeared. (Indeed, they seem to pop up whenever Pacino's name is mentioned, regardless of the specifics of the actual performance.) One wonders whether viewers complaining about Pacino in Dick Tracy have watched the rest of the movie. Every crook with major make-up is performing at the same level; Pacino just has more screen time. Look at Forsythe's Flattop, who's generally spared the need to deliver lines; or Armstrong's Pruneface, with his threats to "rub Tracy out"; or Sorvino's Lips Manlis for the brief time he survives. For that matter, look at Hoffman's Mumbles-the only reason he isn't chewing the scenery is that he never opens his mouth wide enough. (He's still talking the whole time.)

Pacino's performance is perfectly pitched for Dick Tracy, and he demonstrated his power as an actor by holding his own against an army of well-seasoned hams. Even now, almost 20 years later, Dick Tracy has no trouble standing up next to the big hits of today. If anything, there are many films out there that could learn a thing or two from this movie.

Grade: A