Ayla examined her son again, trying to remember the reflection of herself. My forehead bulges out like that, she thought, reaching up to touch her face. And that bone under his month, I've got one too. But he's got brow ridges, and I haven't. Clan people have brow ridges. If I'm different, why shouldn't my baby be different? He should look like me, shouldn't he? He does, a little, but he looks a little like Clan babies, too. He looks like both.

—Jean M. Auel, The Clan of the Cave Bear

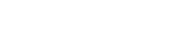

In Secretariat, Disney's more or less family-friendly tale surrounding the principals and events leading up to the eponymous horse's 1973 Triple Crown victory, we find ourselves mired in the troubles of a sports film that aspires to inspire. This is not to say that there's nothing terribly interesting to be seen here; far from it.

The film is self-consciously feminist in many ways. A feminist motif is absolutely appropriate for this particular story, considering that Penny Chenery (Diane Lane, Unfaithful, Under the Tuscan Sun) is a genuine trailblazer for women in the field of horseracing. It's when it tries to exploit this so transparently that it stumbles.

Consider the film's neverending search for a true antagonist. While racing is certainly adversarial in nature, Secretariat isn't so much concerned with Secretariat's victories, which are of course a foregone conclusion to we viewers looking back through time, as it is with the personal trials of the people who invested so much of themselves in the project of the horse. Accordingly, with some unease, the role of antagonist is unsuccessfully assigned to a series of men, including among her own family, to obstruct that curse of biography, the character arc. The last of these, and unredeemed, is also the most awkward, as we are to take Pancho Martin (Nestor Serrano, 24) as a serious threat, when it is quite clear that Penny, Big Red, et al have already won.

Contrast this with the obvious passion for breeding, Penny's true genius, weaving its way through the background of this portion of the larger story. Based in fact or not, Penny recognizes the potential due Big Red from his matriline to become a prizewinning horse, unlike Ogden Phipps (James Cromwell, The Green Mile, Six Feet Under), and thus wins him in a "lost" bet. I can hardly believe that a society with such a grand history of breeding could be so ignorant of the pattern of genetic contributions to offspring in sexually reproducing species, but I'll accept the possibility, and even forgive the fudging of history, for the exciting and valuable lesson it shares: ignorance of reality, in favor of the prejudices of the past, has real costs. Secretariat cannot help but revel in this appreciation, proudly stating in a postscript that the horse's heart was two-and-a-half times larger than that of the average horse. A testimonial to his spirit, some might say, but more prosaically, to the spirit of artificial selection.

In one other way, I must commend Secretariat. The film doesn't have the luxury of the climactic moment. There are, after all, three races in the Triple Crown. Lesser filmmakers would have pared them down to one, giving the others short shrift; perhaps the first race was the real test, or the first two were merely preparations for the final victory. This would have been a disservice, and fortunately, Secretariat exploits the very different conditions of the races to provide three different kinds of presentations, each with its own emotional core.

None of this is to resolve my objections to the silliness sought once too often from trainer Lucien Laurin (John Malkovich, Empire of the Sun, Being John Malkovich), or the soliloquy sought once too often from groom Eddie Sweat (Nelsan Ellis, True Blood). But, perhaps, it is just as far as they could push what is clearly meant to be the heartwarming tale of a horse.